Introduction

Beatriz González (Bucaramanga, 1932) is one of Latin America’s most influential painters. Her work is poetic and direct, critical and alienating. Through the overwhelming visual language of her idiosyncratic paintings, she delivers pointed commentary on Colombian society. By doing so, she preserves memories of events about which most official historians keep silent. War and Peace: A Poetics of Gesture is the first-ever exhibition of her work in the Netherlands and focuses on gestures as vehicles for conveying emotion.

From the start of her career, González has challenged the West’s dominant position in the art world (a major theme of the 2024 Venice Biennale). By co-opting famous Western masterpieces for her own purposes – initially using colours and pop-culture elements drawn from Colombian folk tradition – she advocated for a local style. Later, with the giant curtain entitled Decoración de interiores (which was originally 140 metres long), she turned her attention to the corruption of the Colombian regime and the violence that gripped the nation.

González often finds inspiration in news photos and cheaply produced printed materials. In these flat and fuzzy images, it is mainly poses and gestures that reveal the human drama. This idea is a common thread running through the more than six decades of González’ career. She ‘zooms in’ on the poses people take and alters their context. By doing so, she creates almost graphic compositions which centre on the body language of death, mourning and sorrow, as well as the act of burying victims. The sign-like silhouettes that continuously recur in her work etch themselves into the viewer’s mind. They are a metaphor for the plight of many, both in the Latin American region and beyond.

Critical Appropriations

As a young Colombian painter, González grappled with the hegemony of Western art. One approach involved copying celebrated masterpieces by Velázquez and Vermeer. But she also took her cues from more lowbrow sources like popular Catholic prints and newspaper photos of Colombian and international celebrities. By using enamel paint on metal rather than oil on canvas, she achieved an effect reminiscent of her country’s beloved folk art. For her ‘furniture paintings’, she mounted paintings on ordinary pieces of furniture like beds and dressing tables. Such unexpected pairings lent an ironic and humorous note to her work. From the 1980s on, her artistic practice took on a critical and political aspect in response to the atrocities increasingly being committed by the Colombian regime.

González is intrigued by the photos in mass-produced printed media such as newspapers and magazines. The lack of detail flattens those images, stripping their individuality. The artist makes eager use of that effect in her own paintings, such as in this early example. It is based on a local newspaper photo of a young couple who killed themselves by jumping into the Sisga River in Colombia in order to keep their love pure. That picture inspired the artist to create a graphic, almost collage- like image in which the couples’ hands are symbolically joined together. In this way, González renders the personal universal: her artistic response to the tragedy made an indelible impression on many people.

This twelve-metre-long curtain is González’ first explicitly political work, through which she criticised the government led by Julio César Turbay Ayala, the 25th president of Colombia. Her source was a newspaper photo showing Ayala in a relaxed and festive setting, surrounded by guests who are singing and making toasts, apparently untroubled by the atrocities taking place under his regime. The scene repeats endlessly. The original canvas measured 140 metres long and could be purchased by the metre. González mockingly appointed herself ‘court painter’ – and immediately put an ironic spin on the position. She depicted the powerful leader, but in a way that undermined his authority. The curtain has a symbolic function here as well, both concealing and revealing his tyrannical leadership.

Experimentation and chance are important parts of González’ method. Her ‘furniture paintings’ came about when she looked at an existing child’s bed and suddenly saw a blank surface for a painting. Like the curtains and the wallpaper, these works have recognisable links to everyday life. Her decision connected the meaning of the bed with that of the image. It also marked the beginning of a famous series. For Naturaleza casi muerta (Almost still life), she painted a fallen Christ on the bed base, as if granting Him a moment of rest. This is a tongue-in-cheek reference to a popular sculpture from a well-known pilgrimage site in Bogotá. For Santa Copia (Saint Copy), she combined her own copy of a Madonna and Child (c. 1460) by Filippo Lippi with a dressing table: a swipe at the ‘culture of beauty’ among women.

Mourning

The mid-1980s marked a turning point in González’ work. In response to the corruption, abuse of power, guerilla warfare and drug-related violence afflicting Colombia, themes of mourning, pain and sorrow came to the forefront of her art. Her paintings began to focus on blindfolded eyes, averted faces and beseeching figures on their knees: body language expressing the country’s seemingly eternal state of near-collapse. González wants to make images that do justice to history. Yet at the same time, these images convey human emotions that are felt around the globe – now more than ever.

Manipulating existing images is a key strategy of González’ art. Here, she took inspiration from a popular silhouette of a ‘pin-up girl’: a woman with long, flowing hair who leans back in a seated position. The logo-like image, also known as ‘mudflap girl’, is often seen on the mudflaps of heavy trucks in the US. In the larger-than-life Empalizada (Palisade), González converts that image into a grief-stricken figure leaning on her arms and knees. The result is both an indictment of the violence and a monument to the suffering of women who have lost loved ones. At the same time, however, the artist plays an intriguing game with perspective. While the viewer might feel like a voyeur, those behind the palisade hide their faces.

Ceremonia de la caja (Casket ceremony) is part of the Sin fin series of paintings and drawings from 2010. The idea for the series came from a newspaper photo of three women travelling on public transport, each with a small casket holding the remains of a loved one in their lap. González has painted a scene that evokes the solemn ceremonies organised by the Colombian government for the purpose of returning the remains of civilian casualties – a now all-too- familiar ritual. The artist gave this work the title Sin fin because she feels that ‘the tragedy in Colombia is never-ending’.

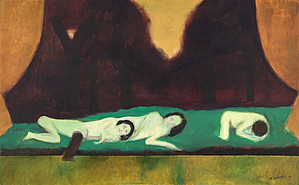

The Lifeless

You might think that gestures are reserved for the living. Yet by painting the blank faces and defenceless bodies of the deceased, González catalogues the body language of the dead. For her, it is not about the specifics or the story behind each victim’s death. She omits the specific context, reducing the image to clean compositions and well-defined planes of colour. Some compositions resemble familiar themes and famous paintings from art history, such as portraits of Roman emperors on a frieze or the Lamentation of Christ. The way in which González appropriates this iconography brings us uncomfortably close to universal emotions and the finality of death.

Entierro en el Museo Nacional (Burial at the National Museum) resembles a catalogue page of gestures and facial expressions conveying pain, revulsion and disbelief. González has ingeniously arranged the various ‘specimens’ so that their outstretched arms are also banners or the edges of a coffin, all at the same time. A yellow shawl appears to flow into one figure’s back. Besides making art, González was a critic and museum curator as well. The title suggests that she found inspiration for her own work in the museum and has incorporated poses from various paintings in its collection. Here, they come together in a brightly-hued landscape of mourning and sorrow.

A life-sized body floats in the water like some sort of terrifying nightmare image. González has limited her composition to three blue-green stripes, with which the oddly bent, lemon-yellow head contrasts sharply. There are no clues as to what has happened. By depicting the figure out of context and in close-up, without explanation, the artist emphasises the finality of this tragedy. As a result, the work not only elicits compassion in the viewer but allows them to feel the powerlessness of the situation. Besides violence itself, González also wants to confront the viewer with the impotence and distress of the surviving loved ones. Through the ambiguous title – corriente (current) refers both to a flow and present time – she emphasises that situations like this are all too common.

Unending Toil

Recovering bodies, digging graves and bearing caskets: González paints the results of violence in Colombia as a seemingly endless series of actions. The artist also turns her attention to those forced to flee. Climate change is driving some groups from their homes, while political climates (such as in neighbouring Venezuela, under the repressive regime of President Nicolás Maduro) are forcing others to migrate. She has based their specific poses, bent under heavy burdens, on sources like newspaper photos of Venezuelans crossing a river while carrying refrigerators and TVs on their backs. The repetitive and graphic pattern clearly implies that these people will not be the last to meet such a fate.

In the early 2000s, Colombian newspapers began printing photos of soldiers and civilians transporting dead bodies more and more often. González was struck deeply by these images. In the 19th century, cargueros (porters) were men who carried tourists across Colombia to show them the country’s magnificent sights. Today, they symbolise the shocking events Colombians must deal with each and every day. González collected newspaper clippings about these cargueros. Inspired by the easy-to-grasp symbols on wildlife crossing signs, she simplified the images to silhouettes. These form the basis for her silhouette drawings and paintings, with Cargueros de Bucaramanga (Porters of Bucaramanga) being a key work in that series.

In 2009, González used the silhouettes again at a cemetery in Bogotá. She screenprinted plaques and placed them in the burial niches of a dilapidated columbarium. By doing so, she transformed the structure into a poignant monument entitled Auras anónimas (Anonymous auras).

War and Peace

‘Art says things that history cannot’, as González often puts it. This assertion reflects her penchant for making latent emotions tangible. In 1981, she created her own version of Picasso’s Guernica. By doing so, she placed the most famous symbol of innocent victims’ despair in the context of her homeland. Forty years later, after the Colombian government and the FARC guerillas signed a peace treaty in 2016, she once again took stock. González saw this as the dawn of a new era, in which mourning and remembrance would go hand in hand with efforts at reconciliation. With the large, loosely draped canvases Telón Guerra and Telón Paz (which once again refer to theatrical and other curtains), the artist visualises the contrast between war and peace.

Telón Guerra (War backdrop) depicts a group of figures on a riverbank. González based this work on a picture showing a group of murdered sex workers. Almost automatically, the unsuspecting viewer is pulled into the unpleasant scene by her warm use of colour and the larger-than-life scale. Telón Paz (Peace backdrop) is based on another photo from the same newspaper. Here, we see musicians celebrating the return of previously colonized land to the indigenous Kogi people. The diptych captures the two extremes of war and peace, which – given the lack of context – could be taking place anywhere.

Guernica (1937), Pablo Picasso’s most famous work, depicts the bombing of the town of Guernica during the Spanish Civil War. Around the globe, the painting became a symbol of the fear and despair of the innocent victims and an indictment against violence. With Mural para fábrica socialista (Mural for a socialist factory), González created her own version of that iconic work. She painted it on wooden panels and exchanged the original black- and-white palette for hues found in the murals of her hometown.

Introduction

The hierarchical caste system of his homeland offers a starting point for the stirring and poetic oeuvre of the young Indian artist Amol K Patil (Mumbai, 1987). Patil focuses on the inherent social inequality of the caste system, particularly in regard to Dalits: the marginalised members of the lowest social classes. Through his work, which consists of intimate and dimly-lit sculptures, drawings and videos, he provides a tangible experience of their wretched position. He emphasises the invisible place they occupy in the city, while hands and feet symbolise the dehumanising labour they perform.

Among other sources, Patil found inspiration for Whispers of the Dust in the architecture of chawls in Mumbai. These lowly dwellings, which originally served as prisons, now house factory workers. After decades, the walls have become saturated with the stories of many generations. Patil’s sculptures echo the randomly shaped cracks and dents in these walls. The interior of the municipal real estate office appears in his installations as well. Here, however, the desk drawers are filled not with paperwork but with sand and dust that seems to whisper.

Patil’s art carries on a family tradition of critical thinking. His father was an avant-garde play- wright and his grandfather practised the ancient art of powada ballads. Often performed by Dalits, powadas are a means of offering social and political critique through poetry and song. Patil similarly incorporates powada melodies and texts in his installations, drawing from both famous balladeers and his own family’s archives.