Introduction

A sports car with cat’s eyes, a poodle on a trampoline and a parade of giraffes – the German artist Raphaela Vogel (Nuremberg, 1988) establishes surprising connections in her work. In her large-scale installations, sculpture, painting, experimental videos and music all flow together to yield enigmatic and unsettling visual presentations in which she herself often plays a central role, together with her dog.

KRAAAN – written with three ‘A’s so as to encompass both the Dutch (kraan) and German (Kran) words for ‘crane’ – offers an overview of Vogel’s work, from early experiments with film to recent installations. The slender construction of a crane relates to her interest in the questions around the idea of hubris, a Greek word which refers to the misplaced pride of mere mortals who dare compare themselves to the gods. That same concept serves as a common thread running through the exhibition, which includes monumental works such as Rollo (2019), with its architectural models that once belonged to a now-defunct theme park.

Vogel elicits provocative questions about the relationships between people, animals and machines, about the privilege enjoyed by artists and about the position of women in a male-dominated world – and art world. While the artist supplies no answers, she intertwines the questions with one another in surprising and humorous ways. Aided by the accompanying video clips and music, she guides you through her work like a modern-day oracle, sowing doubt in connection with existing ideas and deeply ingrained patterns.

Male dominance – in both the art world and society – is an important theme in Können und Müssen. The anatomical model of a penis, drawn by a team of skeletal giraffes, bears signs of various maladies. Is this Vogel’s way of announcing the end of the era of male dominance? Or are the giraffes actually being restrained by the male member? Do the skeletons appear vulnerable? Or do their long necks, alternately bent and held assertively aloft, instead depict a potent virility? Vogel elicits questions without providing any answers. As a result, Können und Müssen could be taken as both jest and warning.

Vogel originally trained as painter but quickly became interested in action painting and performance art. She began recording herself at work in her studio in all kinds of unorthodox ways: by attaching ‘proto-selfie-sticks’ to her limbs, using action cameras and filming herself with drones while attempting to tame the camera like some sort of wild animal. These experiments later evolved into hypnotic videos in which she is not only the primary subject, but – as the one wielding the camera – also the one determining how she appears to the viewer.

Karmerabruch

Drahtwickel

Psycogräfin

With weathered architectural models of iconic structures like the Arc de Triomphe and the Tower Bridge, Vogel challenges the old Western ideals. Were these too arrogant? In the accompanying film, which – in being shown on the wide screen – resembles the neon signs of urban advertising, those faded ideals seemed to have inspired her. Here, she connects that pride and arrogance to the role of art and her own artistic production. We see the artist scaling a crane while filming herself with a disorienting 360-degree camera. It is a risky undertaking for which there is no prior demand and that has no clear goal – just like making art. Once she arrives at the top of the crane, the image begins to spin like a dizzying vortex. At that point, we hear Vogel singing her own rendition of Nina Simone’s cover of Ain’t Got No, I Got Life, in which she cheerfully takes stock of what she does and does not have. This energetic and existential inventory both tempers and kindles her own vital arrogance.

For Vogel, animal hides provide a vital ground for her paintings. Because these hides are reminiscent of ancient rituals or slaughterhouses, they are charged with a completely different meaning than a traditional stretched canvas. In The (Missed) Education… Vogel paints a collection of knowledge graphs onto the hides. By doing so, she explores the question of how one might objectively depict information. Together, as it were, the hides form one big ‘mindmap’ of the artist’s knowledge and interests, which range from Karl Marx to the equestrian sport of dressage and from jazz to pop culture.

Standing within this open dome, you hear a vague growling sound. It is as if the tiger-like creatures that menacingly creep upward along the tubes have come to life. Vogel is interested in how the body responds to external stimuli. Low-frequency sounds – like those here, which are produced by rumbling empty stomachs – are thought to encourage digestion. By manipulating the noise to create a technical sound, Vogel forges a link between the organic and the technological. With the title, she refers to a now-surpassed unit of measurement for quantifying information on a computer and suggests that computer data must be digested.

For Vogel, creating art was initially a way to claim her own space as a woman in a world (and art world) dominated by man. The short film Einparken (Parallel Parking), seems to offer direct and humorous commentary on this. In the film, the glass of a storefront window reflects Vogel’s attempts to manoeuvre a large camper van into a tight parking spot. It is as if the reflection is casting not only the scene but our own stereotypical assumptions back at us. Steel tubes as a metaphor for installation, construction and connection are a recurring element in her work. Here, they demarcate the space in a literal way as well.

Through these medallions, each held in a decorative frame, Vogel explores the meaning behind the concept of a ‘motif’, which is a recurring visual element. Is it possible to interpret such a motif without being influenced by the material, the style and the visual signature of the artist? In Würde / Motiv, Vogel attempts to assign a more general meaning to motifs from her own oeuvre. At the same time, by painting them on reflectors, she also suggests that the meaning of each motif is ultimately determined by the viewer.

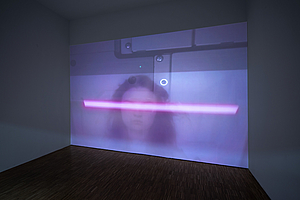

The diffuse boundaries between human, animal and machine serve as a common theme running through Vogel’s oeuvre. In the two-part installation A Woman’s Sports Car, for instance, the engine appears to function like a beating heart, while its shiny covering is displayed elsewhere in the exhibition. In a looped video clip, projected from inside a birdcage – a play on the artist’s surname, which means ‘bird’ – Vogel appears like a mythical siren, luring the viewer into a new and disorienting world. In this way, she urges the viewer to let go of their habitual ways of thinking. You could also interpret it as a plea for art in general. Her reference to Hygeia, the Greek goddess of health, suggests that this is good for both body and mind.

Nothing in Vogel’s oeuvre is unambiguous. The same goes for Uterusland, the video in which she zips down a waterslide holding an extremely lifelike doll. The footage is shaky and the sound resembles the rhythm of a person breathing. It is as if Vogel has recorded an impossible re-enactment of her own birth – as a person, an artist, a woman and a mother. The industrial milking machines in this installation elicit questions about the role of women in society but also about the practices of intensive livestock farming.

The A Woman’s Sports Car merges desire and seduction with animals, power and artistic identity. The installation is semi-autobiographical in nature. The central object here is the Spitfire, a small sports car that claims the space like a cat. In its field of vision – and ours – appears Vogel’s dog, Rollo, who himself proceeds to ‘mark’ a park. Through this dreamlike phenomenon (the otherworldliness of which is due in part to the use of a 360-degree camera lens), Vogel compares the act of making art and the competition in the art world with the territorial urges of an animal. Meanwhile, the car – a model once marketed as ‘a woman’s sports car’ – shows off its curves atop a rotating platform. To create the mysterious tune, Vogel manipulated the soundtrack of an advertisement for Chanel perfume, while the letters ‘M AMA’ on the licence plate refer to the Spitfire belonging to the artist’s own mother.

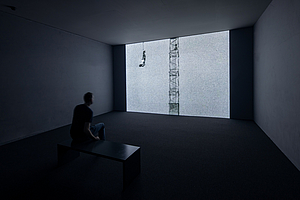

Okay, Okay is a 90-minute music video (before there was such a thing) featuring New Wave and Post-Punk. The rough footage from West Berlin and the Ruhr region is seamlessly aligned to the music. Together, like Sander’s film, they embody the Zeitgeist that existed around 1980, a period when the housing crisis and feverish construction (the crane) seemed to go hand in hand. One might also see a parallel with the current era. Okay, Okay established unconventional connections and is both unsettling and reflective in nature. The same could be said of Vogel’s oeuvre.

In this socially-engaged film by feminist activist and director Helke Sander, a woman scales a construction crane in Hamburg with her two children. The pamphlets she drops explain that she plans to jump if she does not have an affordable place to live by midnight. Sander based her film on a true story. For Vogel, the film served as a source of inspiration for her work Rollo.

Raphaela Vogel in her own words

Trailer

#2 - Songs and Sounds

#6 -Heraldic Animals in Wildlife

#1 - City and Horizontality

#3 - Moving Image Times Two

Museumcafe

Explore the menu of our cafe.

About Vogel

More information about the German artist.