This spring De Pont will be showing the complex project Carbon by the German born artist Lothar Baumgarten. It is for the first time in many years that work by Baumgarten is being shown again in the Netherlands. Prior to this he has exhibited at, among other places, the Van Abbemuseum Eindhoven (1982) and the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam (1985).

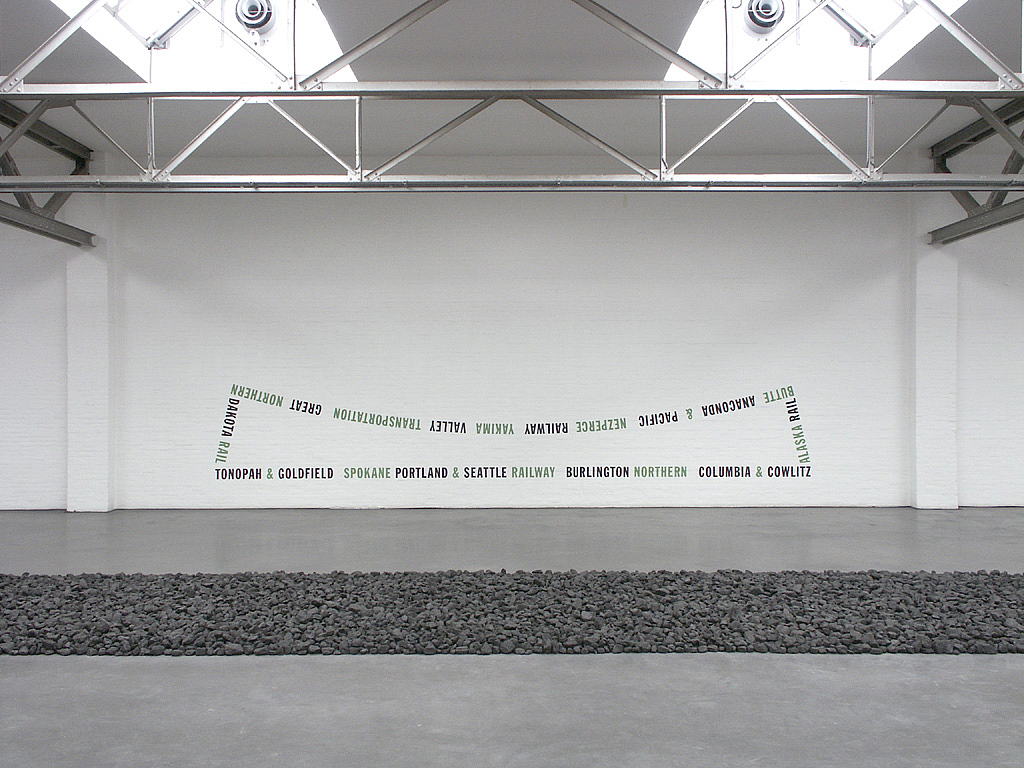

Lothar Baumgarten (Rheinsberg, 1944) has become internationally known through his subtle culture critique. His often side specific work widely reflects a great concern on ethnographic stratum and local historic circumstance. The extensive body of Carbon concists of more than one hundred gelatine silver prints. There subject matter is defined through railway track structures, railroad bridges, semaphore systems and the remote endlessness of the North American continents landscape. They document the pioneering spirit of settling a landmass from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean. In addition to the photographic work a series of wall drawings will be realized in situ. There geometrical configurations are build out of the polyphonic names of those railroad lines and will be drawn directly on the walls. The given architectural context of the exhibition space determins there placement by shape, color and size. As part of the exhibitions structure it self, there will be the presentation of the famous book Carbon, which represents in its results so far the peak of the over years developed collaboration between Walter Nikkels and Lothar Baumgarten.

Carbon came about during Baumgarten’s first survey on territorial expansion and setling of the West in 1975. An invitation by the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles in 1989 made him reconsider his frequent research. Then in four and a half month the photographic documentation was completed and the initial presentation of the project was held there in 1990. The exhibition did not show a single photograph, it only consisted of one, the whole space structuring wall piece. Initially the photographs were meant as guidance for the project and only to be used in the book. So was a large number of short stories written and were ten of them published in the insert of Carbon.

For Lothar Baumgarten the polyphonic names of the railroad lines embed their drama and tell about the history of meeting and clash by different languages and concepts of thought. They call to mind, on the one hand, the Native societies by their tribal and place names, on the other, they mark the advances of the unstoppable European settling of the continent.

This advance can be discerned on the basis of the railway lines that extend across the country like a giant web. Many of the railroad tracks and embankments have been built by Chinese laborers. As such, these also constitute the forgotten story of a third population group.

The photographs show railway tracks, trains, locomotives and viaducts, but also vast landscapes, run-down train yards and dreary industrial zones. Carbon offers no nostalgic railroad romance; it provides a clear account of the consequences of ‘opening up’ Indian territories. The endless freight trains seem to illustrate, above all, the excessive consumption of the new inhabitants, and in this respect the title Carbon refers to the continuous need for fuel that is meant to satisfy this hunger. And Carbon names the method to analyse the age of archeological finds.

The deterioration of this railway system (surpassed by other systems of transport and new production techniques) indicates the fleeting nature of this culture aimed at consumption and expansion. Baumgarten juxtaposes this linear process of ‘progress’ with the cyclical awareness of time held by the native peoples, who for centuries have geared their societies to the alternating of seasons and the process of natural changes. But these ancient peoples and cultures seem to have been devoured once and for all, and what remains are their names, which live on in the network of the railroads: Cheyenne & Northern Railway, Apache Railroad, Keokuk Junction or Monongahela Viaduct. Other names continue to exist only as geographic designations: Potomac River, Coconino County and Chemehuevi Mountains.

With his account Lothar Baumgarten also seems to be following the trail of a typically American tradition of landscape photography. The rugged vastness of the American West has fascinated countless artists and photographers. Nineteenth-century pioneers such as William Henry Jackson and Timothy O’Sullivan photographed the landscape, and Andrew Russell and William Rau chronicled the building of the first railways. Later, the photographs of Walker Evans and Robert Adams became icons of the American landscape. More recently, the work of James Welling has provided a sequel to classic documentary photography with his Railroads Series.

The painstaking manner in which all of these photographers have portrayed their subjects similarly characterizes the work of Lothar Baumgarten. His shots are carefully chosen in terms of vantage point, composition, lighting and detail. This intent precision is moreover evident in the writings that constitute a significant part of his work. Occasionaly Baumgarten uses names and words as prominent visual elements. His wall drawings consist of combinations of words that have an imposing effect due to their format, typography, composition and color scheme. The words are native names and are highly suggestive in sound and meaning. Sometimes the wall drawings work as pictograms; with the work Bridge (1989) the names have been placed in such a way that they form the image of a bridge and the letters adopt the rhythm of pillars. For the wall drawings of Carbon, Lothar Baumgarten took inspiration from the specific visual language of railroad typography. The study of such language and communications systems is an essential part of this particular work. Like an ethnographer, he examines the ways in which cultures identify with these systems, and as an artist he manages to transform them into independent images in a poetic and associative manner.

Lothar Baumgarten (Rheinsberg, 1944) has become internationally known through his subtle culture critique. His often side specific work widely reflects a great concern on ethnographic stratum and local historic circumstance. The extensive body of Carbon concists of more than one hundred gelatine silver prints. There subject matter is defined through railway track structures, railroad bridges, semaphore systems and the remote endlessness of the North American continents landscape. They document the pioneering spirit of settling a landmass from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean. In addition to the photographic work a series of wall drawings will be realized in situ. There geometrical configurations are build out of the polyphonic names of those railroad lines and will be drawn directly on the walls. The given architectural context of the exhibition space determins there placement by shape, color and size. As part of the exhibitions structure it self, there will be the presentation of the famous book Carbon, which represents in its results so far the peak of the over years developed collaboration between Walter Nikkels and Lothar Baumgarten.

Carbon came about during Baumgarten’s first survey on territorial expansion and setling of the West in 1975. An invitation by the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles in 1989 made him reconsider his frequent research. Then in four and a half month the photographic documentation was completed and the initial presentation of the project was held there in 1990. The exhibition did not show a single photograph, it only consisted of one, the whole space structuring wall piece. Initially the photographs were meant as guidance for the project and only to be used in the book. So was a large number of short stories written and were ten of them published in the insert of Carbon.

For Lothar Baumgarten the polyphonic names of the railroad lines embed their drama and tell about the history of meeting and clash by different languages and concepts of thought. They call to mind, on the one hand, the Native societies by their tribal and place names, on the other, they mark the advances of the unstoppable European settling of the continent.

This advance can be discerned on the basis of the railway lines that extend across the country like a giant web. Many of the railroad tracks and embankments have been built by Chinese laborers. As such, these also constitute the forgotten story of a third population group.

The photographs show railway tracks, trains, locomotives and viaducts, but also vast landscapes, run-down train yards and dreary industrial zones. Carbon offers no nostalgic railroad romance; it provides a clear account of the consequences of ‘opening up’ Indian territories. The endless freight trains seem to illustrate, above all, the excessive consumption of the new inhabitants, and in this respect the title Carbon refers to the continuous need for fuel that is meant to satisfy this hunger. And Carbon names the method to analyse the age of archeological finds.

The deterioration of this railway system (surpassed by other systems of transport and new production techniques) indicates the fleeting nature of this culture aimed at consumption and expansion. Baumgarten juxtaposes this linear process of ‘progress’ with the cyclical awareness of time held by the native peoples, who for centuries have geared their societies to the alternating of seasons and the process of natural changes. But these ancient peoples and cultures seem to have been devoured once and for all, and what remains are their names, which live on in the network of the railroads: Cheyenne & Northern Railway, Apache Railroad, Keokuk Junction or Monongahela Viaduct. Other names continue to exist only as geographic designations: Potomac River, Coconino County and Chemehuevi Mountains.

With his account Lothar Baumgarten also seems to be following the trail of a typically American tradition of landscape photography. The rugged vastness of the American West has fascinated countless artists and photographers. Nineteenth-century pioneers such as William Henry Jackson and Timothy O’Sullivan photographed the landscape, and Andrew Russell and William Rau chronicled the building of the first railways. Later, the photographs of Walker Evans and Robert Adams became icons of the American landscape. More recently, the work of James Welling has provided a sequel to classic documentary photography with his Railroads Series.

The painstaking manner in which all of these photographers have portrayed their subjects similarly characterizes the work of Lothar Baumgarten. His shots are carefully chosen in terms of vantage point, composition, lighting and detail. This intent precision is moreover evident in the writings that constitute a significant part of his work. Occasionaly Baumgarten uses names and words as prominent visual elements. His wall drawings consist of combinations of words that have an imposing effect due to their format, typography, composition and color scheme. The words are native names and are highly suggestive in sound and meaning. Sometimes the wall drawings work as pictograms; with the work Bridge (1989) the names have been placed in such a way that they form the image of a bridge and the letters adopt the rhythm of pillars. For the wall drawings of Carbon, Lothar Baumgarten took inspiration from the specific visual language of railroad typography. The study of such language and communications systems is an essential part of this particular work. Like an ethnographer, he examines the ways in which cultures identify with these systems, and as an artist he manages to transform them into independent images in a poetic and associative manner.