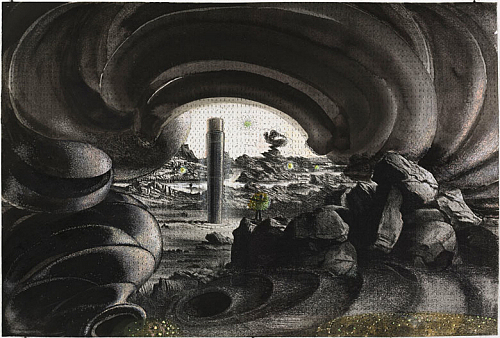

De Wit is a masterly draughtsman. The applied perspective, the atmospheric effect of light and the sculptural rendering of subjects invite us to enter the virtual space of his drawings. This is an expedition that requires time: the longer we look, the more we discover. The enormous size of his work is scarcely sufficient to accomodate its wealth of motifs. Scale and proportions frequently mislead the eye, and motifs drawn in great detail often prove to be unfathomable. Yet the inventiveness and technical skill with which they have taken shape make them surprisingly real. Here collapsed structures, steel constructions meandering like vines, are on equal footing with thorny formations and stalks of plants, wasps' nests, birds, snails and mudskippers. In his most recent drawings, the organic has largely displaced the architectonic. The panoramic perspective has given way to a zoomed-in view. Not often are we so inescapably confronted with a fat toad as in two drawings from 2012: simmeringly red in one work, immaculately white in the other. Anthropomorphic figures are also beginning to appear now. De Wit has derived their shapes, as he often does, from something that he has come across in day-to-day reality. While cycling from Maastricht to Liège, in the mooring posts along the Quai de Caster he discerned the human form that he had been seeking. They stood there in a row like motionless and anonymous guards, submerged to their shoulders in the ground, gazing at the water. In Toad the creature crawls over these mooring-post shapes, oblivious as he leaps from what could be humans. The same mooring-post shape was also the point of departure for a number of wax models that are being shown for the first time in this exhibition. One of them has, in front of its face, a megaphone which directs and defines the line of sight. Unbiased and careful observation is one thing, but contemplating that which is observed is another. That reflective aspect plays an important role in De Wit's art. His drawings can be interpreted as allegorical representations of what goes on in the world. In that respect, but also in terms of the visual language he employs, they belong to a tradition that goes back to sixteenth-century artists such as Pieter Bruegel. The religious or moral message contained in many of Bruegel's works has, with De Wit, become much more ambiguous import. He creates a world in which ambiguity predominates, a world which is both fascinating and repulsive. In that world man plays merely a subordinate role. He has become part of a movement that he has not started and cannot control; life is like a plot whose secrets will never be revealed. De Wit opts for the ambivalent and equates that field of tension with a switch caught between the 'on' and the 'off' positions. It is in that paradoxical situation where both forces are in effect—referred to in the title of his exhibition as In the On-Offs—that he wishes to operate.

website of the artistAbout ten years ago Hans de Wit (Eindhoven, 1952) abandoned painting and began to focus on drawing. Since then he has been producing drawings, in charcoal and pastel, that can rival a substantial painting in terms of size. Aside from six of these works, De Wit's exhibition in the project space includes a number of preparatory studies in which he experiments with the possibilities of his instruments and materials.